Shenzhen I/O Tetris

Background

One of the missions in Shenzhen I/O is to create a game in the sandbox.

Intimidated by the idea of drawing something custom for the LCD screen, I thought about making Tetris with the default block matrix.

As that is obviously impossible, I went to skip the mission.

Just before the bar filled up, I stopped. The text on this button believed in me. Could I really betray it? Could I sit there stone faced, lying through my mouse finger to it? The JRPG heroes and moral-of-the-story-having cartoons and sitcoms of my childhood raised me better than that.

There was only one honorable thing to do: a hard work montage.

Phew! Now, let me ruin the pace we’ve set by explaining everything in excruciatingly boring detail.

Major challenge: storing more than one anything

Processors have only one working register: acc. The larger ones add dat, which can only be set with mov. That means to perform operations on the value of dat, you must clobber acc, so even the big processors can only effectively store a single value.

mov dat acc

add 1

mov acc dat

dgt and dst

dgt and dst make it possible to isolate individual digits. Registers can hold three digits.

A falling tetris piece has three values that change while it’s falling: the column (X), the row (Y), and the rotation.

There are only 4 possible rotations for a piece, so that’s easy to fit in a digit. The default LCD matrix is 10x12, so X already fits in a digit, and Y can fit in a digit if we give up the bottom two rows.

Thus we can store our whole state in one register: the left digit is the rotation (0-3), the middle digit is the row (0-9), and the right digit is the column (0-9).

To move a piece right or left we just add 1 or sub 1, to move it down we add 10, and to rotate it we add 100.

To convert this number to a cell on the matrix, we remove the rotation (dst 2 0) and add 1.

Digits as bits: it’s all 1s and 2s

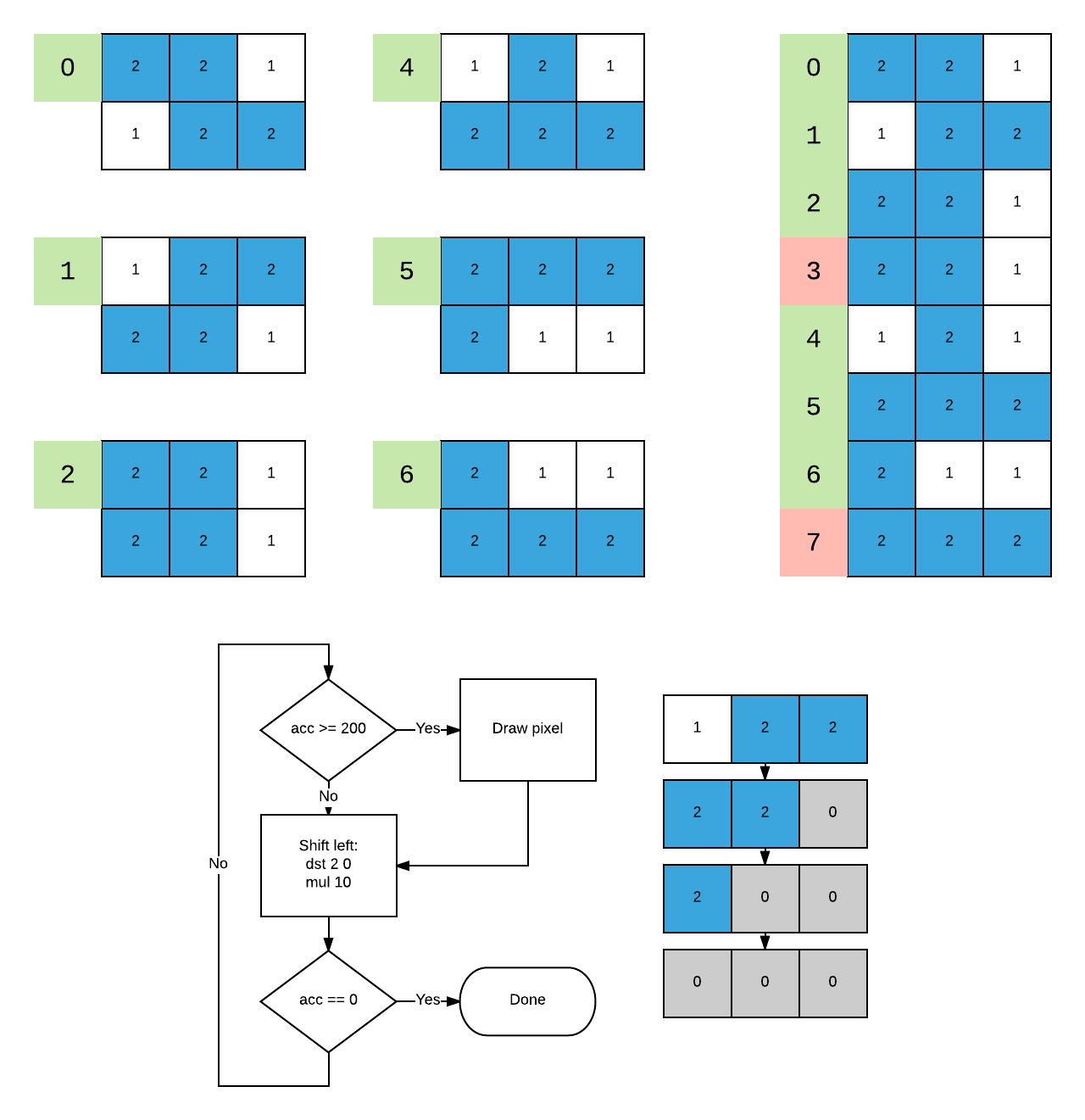

We can represent all but the line piece with 6 bits. Using 1 for “on” and 0 for “off” is natural, but using 2 and 1 makes it easier to decode.

Notice how most pieces share a row with another piece. This lets us squish them together when we store them in a ROM chip. This did not end up being useful, but it is neat.

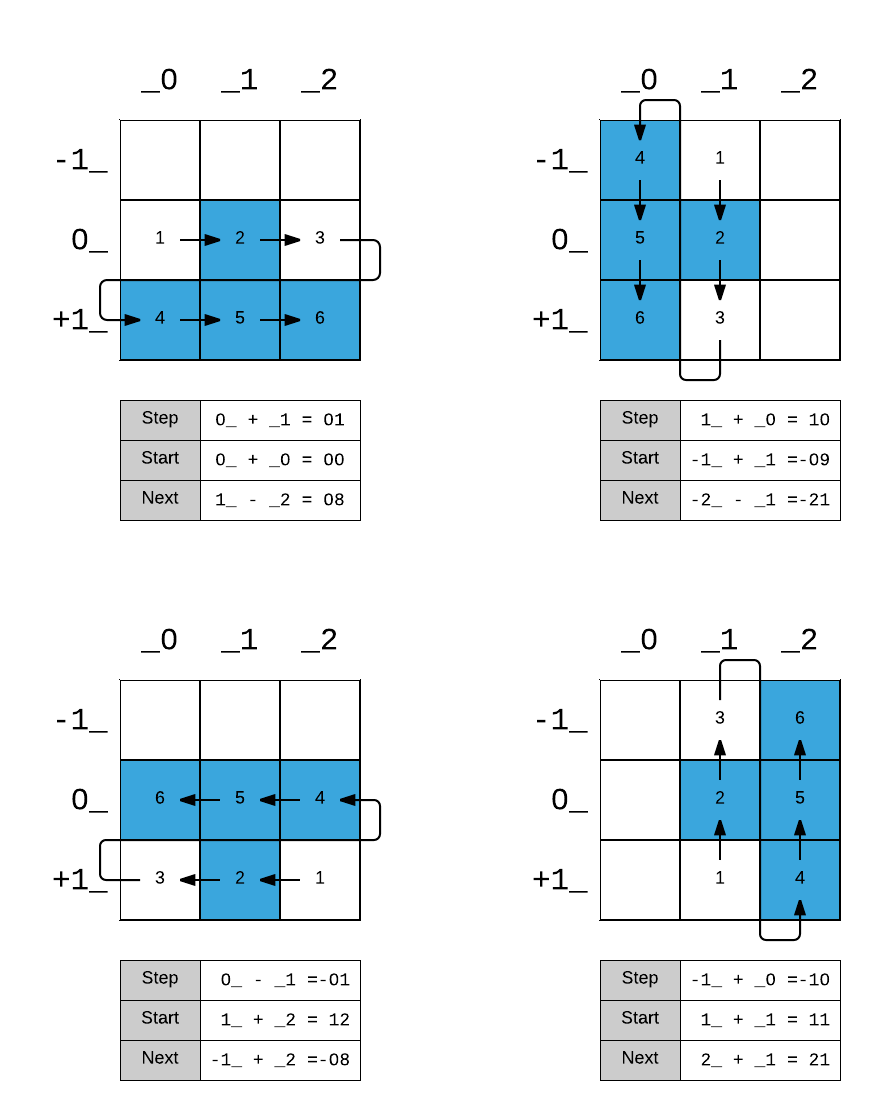

We can step through these bits different ways to render different rotations:

Bits as bits

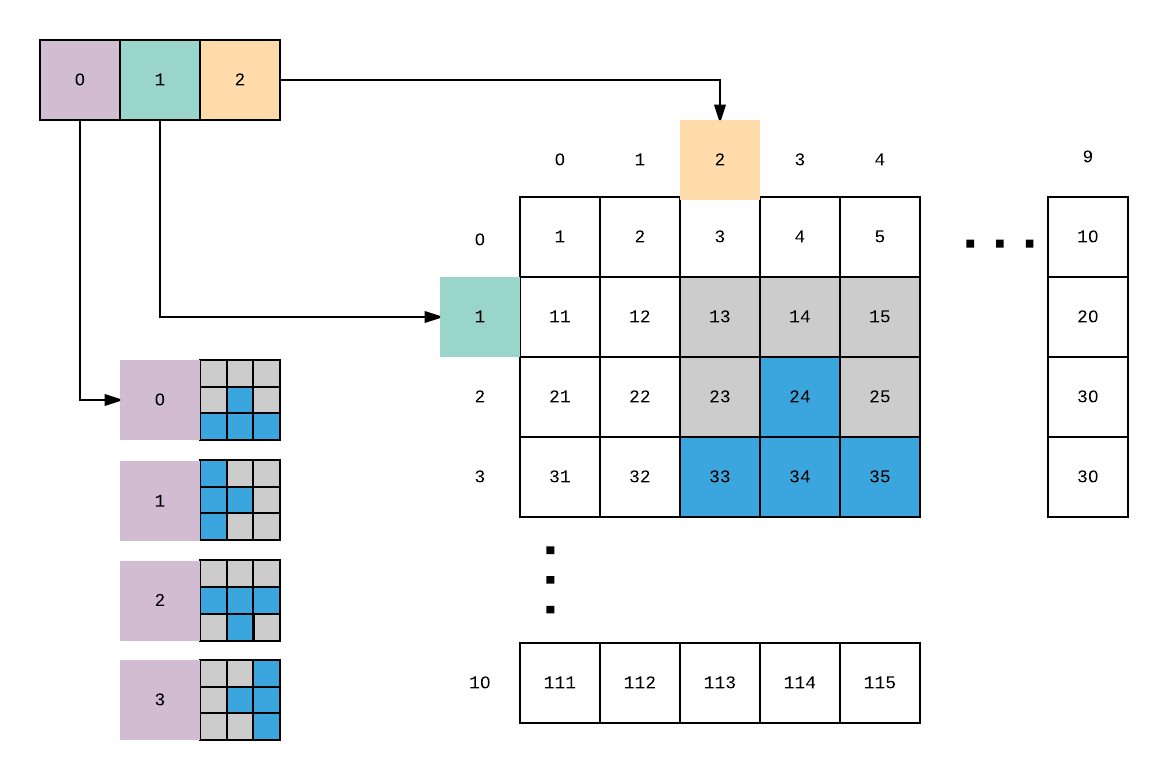

To determine when you’ve run into a piece that’s already in place, we need one bit for every space on the board. Since we decided the board is 10x10, that means we need 100 bits of storage.

The RAM module has 14 cells, which multiplied by 3 digits give us 42 bits of storage. Even if we used two we don’t have enough space to store the whole state of the board.

If we had some way to use binary numbers, we could store three bits per digit using values 0-7, which would give us 9 bits per cell for 126 total bits of storage.

If we then give up a column on the board, each cell can store a whole row. This lets us use one digit to pick a memory cell and one digit to pick a bit, and makes clearing completed lines very easy.

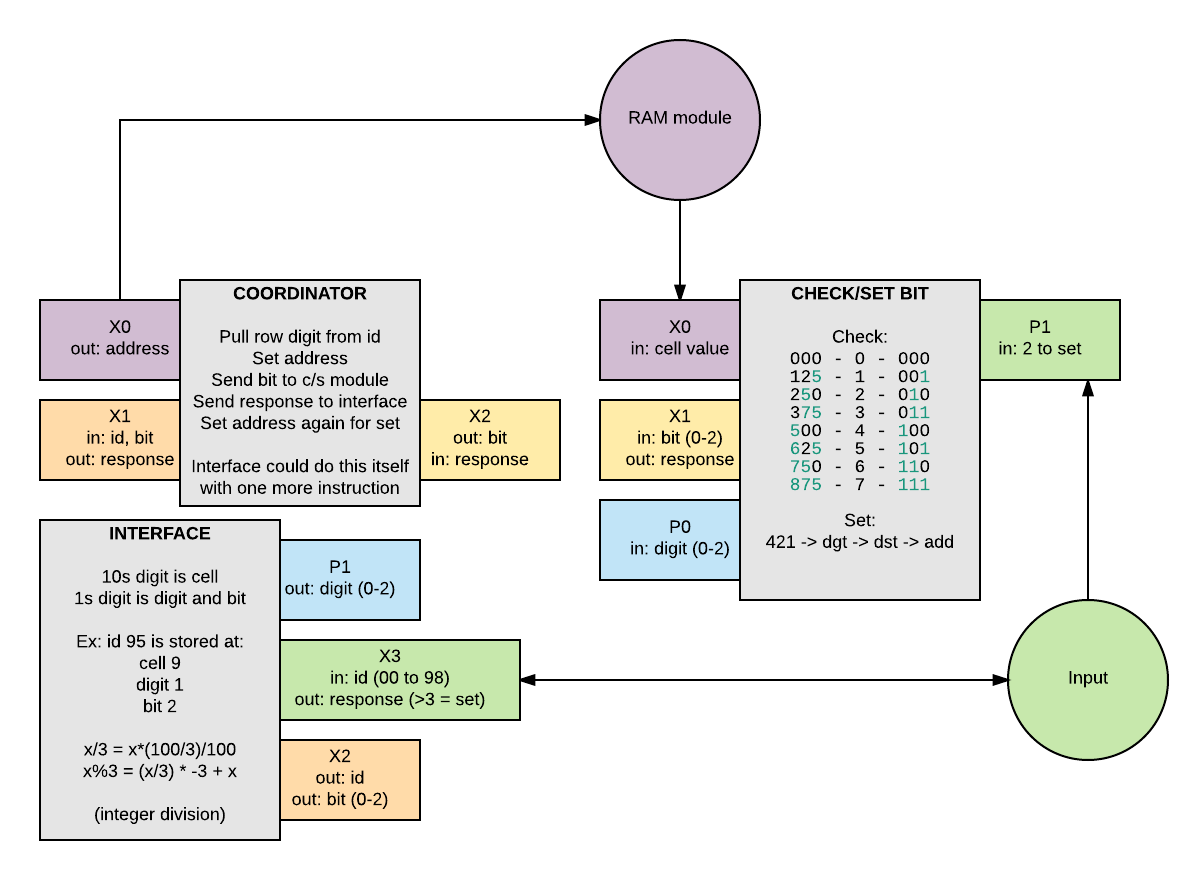

There’s no div instruction, but we can divide a single digit by 3 with mul 34 and then dgt 2.

To convert the digit 0-7 into its component binary bits, we can multiply by 125. A set bit is indicated by a digit greater than 3 in the result. Since it is not any more expensive for callers to tgt reg 3 than teq reg 0, we don’t need to interpret it here.

Putting it all together

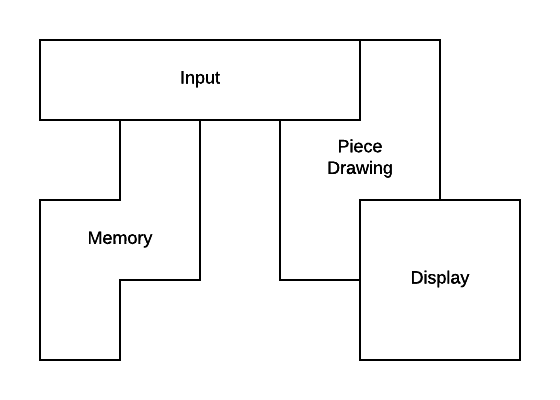

Download the working game here. Left and right move, up rotates. The game ends when it crashes. There’s still plenty of room to optimize and add more. The board is laid out roughly like this:

Here is a video of it in action: