SQL Injection and You

A few months ago, I was approached by Pixeleen Mistral, managing editor for The Alphaville Herald (NWS). She had gotten a reputable tip about a security problem on the website of a popular third-party service for Second Life, and asked if I knew anything about it. The service in question was BanLink, which provides a way for groups in Second Life to share their ban lists. Since the whole point of the service is ostensibly to hinder griefers, it seemed like a pretty hot target for exploitation, and a security vulnerability was potentially big news.

The problem ended up being SQL injection: the ability to modify the queries the website makes to the back-end database. SQL injection is among the most prevalent and most dangerous security problems in web applications. OWASP’s top ten list placed injection flaws at 6th place in 2004, 2nd place in 2007, and they’re going to be 1st place in 2010. This particular application was vulnerable to injection in pretty much every single parameter on every single page, and any errors from the database were reported in full. As far as these things go, it was a gold mine.

As well-known and documented as SQL injection is, it’s still incredibly common. The problem is especially bad in PHP, where writing queries directly is the norm and there are thousands of tutorials which teach unsafe practices. Here is one that many flash game authors use.

Amusingly, the problem was listed as an unimportant known issue on the BanLink wiki:

Punctuation Charachters [’,] in the group name aren’t handled properly, and cause problems

Details: This is an HTML thing. Special charachters aren’t being handled properly.

Workaround: Don’t use special charachters. Long-term solution is to have the system gracefully handle special charachters, either by allowing them, or by discarding them.

(From the SL BanLink wiki.)

Responsible Disclosure

Pixeleen and the person who discovered the vulnerability were unable to contact the two administrators of the service, so determining the impact was difficult. I had pretty regular contact with one of them in the past, but I was also unable to get any kind of response. Both of them seemed have been missing for months, and the service was more or less abandoned.

When data is at risk and the administrators are missing, it can be hard to figure out a moral course of action. Ignoring it and doing nothing leaves all the users unknowingly at risk, but disclosing it publicly potentially exposes them to even more risk. Even when the administrators aren’t missing, it can be hard to spur them into action without hard evidence of a serious problem. I knew that word was already spreading, and that the Herald was about to go public with the information, so I set out to see how much I could get the site to give me.

Hacking the Internet

One thing that makes successful exploitation of a SQL injection vulnerability tricky is the location of the injected string. Some SQL servers will let you abandon or terminate the statement you broke into and begin a new one, but often you have to figure out a way to manipulate a query from somewhere inside the WHERE portion. There are numerous tricks for various database servers. Since every parameter was exploitable on the site, it was really just a matter of finding the page that formatted the output the nicest.

Another hinderance is that the error messages are often not exposed to the user. This makes it harder to craft a malicious query, because if something goes wrong, you won’t be told what it is.

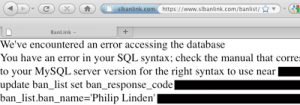

No such trouble on the BanLink website.

Thanks to this error message, you can simply use the pattern ‘ and 1=2 union select … – to replace one select with another, and keep trying until you get the syntax and number of fields right. With MySQL5’s information_schema database, you can use this trick to map out all the tables and columns available, and with that, you can get everything.

The Take

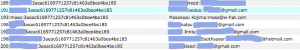

Names, passwords, email addresses; 100% of the data the site had, anyone could view and even modify. Even without access to the members area of the site.

Storing Passwords For Dummies

When storing user passwords, most websites use a one-way hash function to turn the password into a series of otherwise random bits. This allows them to check your password without actually knowing your password: they can just apply the same function to your input, and see if the results match. There are a handful of functions that are commonly used, notably: MD5, SHA, and Blowfish. MD5 is “broken,” which, in cryptography, basically means someone has found a way to determine what input produced a given result faster than simply trying every single possibility (brute force).

Broken or not, the speed of brute-forcing a hash can be vastly improved by employing Rainbow Tables. They can be difficult to understand, so it is easiest to just think of them as an efficient way to try every single password once and store the results for later. If you use a password that is fewer than 8 characters, someone with the right rainbow table could take the result of a ‘one way’ hash and turn it back into your original password in a matter of seconds.

One way to mitigate this kind of attack (and brute force attacks in general) is to use a random string of characters called a ‘salt’ in addition the password when creating the hash. The salt is stored along with the resulting hash; it’s needed to recompute the hash when checking it later. It’s not secret, it’s just there so you can’t compute all the possibilities in advance. With a long enough salt, even a 1-character password can become safe from pre-computation attacks.

BanLink stored unsalted MD5 hashes of passwords, which is about as good as storing them in plain text.

This Is Where You Come In

When this exploit was revealed, some people confessed that they had foolishly used the same password on the BanLink website as they used to access their email. The same email that was exposed with their password. Once an attacker has access to somebody’s email account - especially with their original password, so there is no indication of intrusion - they almost always have access to everything. Nearly all websites will let you reset your password if you can receive an email they send you. Even some banks will let you in this way. Even if you re-use other passwords, you should never use your email password anywhere else. No matter what.

With information about the full impact of the exploit, another user of BanLink was able to convince the company hosting the website to call the owner directly, and the BanLink website was taken down a few hours after the Herald article was posted. As of 2009-12-14, it is still down with an “under maintenance” message, but the back-end services are reportedly still functioning.

nice job